“I see two chameleons by that root…can you find them?” asked our guide Claudio, pointing to a patch of leaf-litter no more than four inches wide. Squinting, our noses almost touching the ground, Chris and I searched until we eventually gave up. Grinning smugly, Claudio picked them up and placed them on our hands. The damage to our egos lessened slightly as we admired the tiny brookesia, an endangered species of chameleon no bigger than the tip of my thumb and perfectly camouflaged to match the leaf litter.

Madagascar, located 300 miles off the southeast coast of Africa, is an island of many such wonders. Though it is the fourth largest island in the world, it contains less than 0.5% of the Earth’s land surface area but houses nearly 5% of the world’s biodiversity. Approximately 95% of Madagascar’s reptiles, 89% of its plant life, and 92% of its mammals existing nowhere else on Earth, making it one of the top five global biodiversity hotspots. This extreme biodiversity stems from Madagascar’s isolation from major continents and its unique topography. It split from Africa over 160 million years ago and then subsequently split from the Indian block 80 million years ago, so over the past 80 million years evolution on the island has been allowed to have a bit of fun. In terms of topography, there is a mountain ridge running down the middle of the island so that rainforest covers the east coast, but everything on the west is a rain shadow. This creates a fantastic range of environments, from very wet to very dry, to which species can adapt.

Some of the most impressive animals in Madagascar include the lemurs, found nowhere else, including the giant indris and dancing sifakas; color-changing chameleons; spiky streaked tenrec; helmet vanga; and giraffe-necked weevil. This is just a tiny sliver of the enormous variety of mammals, reptiles, and amphibians that share the island with over 11,000 known plant species, and a vast unknown quantity likely still remain undiscovered; from 1999 to 2010 alone, scientists discovered 615 new species in Madagascar, including 41 mammals and 61 reptiles.

The diversity of the island is not limited to its plants and animals, but is evident in all aspects of Madagascar’s culture. Home to more than 21 million people, over 20 ethnic groups coexist on the island with a wide array of faiths and customs. The Malagasy may look Indonesian, African, or Arabic, depending on which part of the country you travel to, as descendents of settlers from Borneo and East Africa with cultural influences from Southeast Asia, India, Africa, and the Middle East. Their common language, Malagasy, is most closely related to a language spoken in southeast Borneo, and many people also speak French, thanks to the colonial influence. A majority of the population—80 percent of which is estimated to live below the poverty line—depends on subsistence farming for survival, ranking it as the eighth poorest country in the world, with the average citizen living off less than a dollar per day. Poverty and a rapidly growing population is putting an ever-increasing strain on Madagascar’s natural resources, leading to rapid destruction of the forests for logging and agriculture. Over the past 25 years, Madagascar has lost more than 1 million hectares (2.5 million acres) of forest, and in the aftermath of a coup in March 2009, the rainforests were pillaged for hardwoods such as rosewood, destroying portions of some of the island’s most biologically diverse national parks – including Marojejy, Masoala, Makira and Mananara. This is also taking an extreme toll on the animals who depend on the forest for survival – roughly 40 percent of the country’s reptile species are now threatened with extinction, and lemurs as a group have been labeled by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature as the most endangered group of mammals on the planet, with 94% of all lemur species classified as either “endangered” or “critically endangered”.

Because they have adapted to such specific habitats, each of the country’s many parks more or less contains its own unique set of plants and animals, which, due to the extreme deforestation, are generally easy to spot. This makes deciding which part of Madagascar to visit quite a challenge. When planning a trip, it is also important to consider that while there are many places of interest, traveling between destinations is its own adventure. The country has very few roads, fewer of which are paved, so driving to most parks is only possible by renting an expensive 4×4 vehicle and experienced driver, and it can take as much time to get between parks and cities as the visit itself – usually days. The alternative is to fly on Air Madagascar, the government’s airline, which is outrageously expensive but when on time, fairly quick. However, there are not that many airports so any trip is bound to involve some driving.

The typical tourist route follows the RN7 southwest from the capital, Antananarivo (“Tana”), and hits many highlights of the country such as Ranomafana, Andringitra, and Isalo national parks, ending in the beach town of Tulear on the west coast. A relatively straightforward and relaxing trip was tempting, but knowing that many of Madagascar’s species may not survive much longer, and wanting to see them in an authentic habitat, we were drawn to the relatively wild and unexplored Masoala peninsula, containing, among others, Masoala National Park, Makira National Park, Marojejy National Park, and Anjaharibe-Sud Reserve. We were warned that this was one of the wettest areas in the world, and July and August are still the wet season, but at the risk of never making it there if we put if off now, we decided to go ahead. After pouring over the Brandt travel guide, anything we could find on the internet, and a book on Madagascar Wildlife, and emailing back and forth with numerous local guides, we settled on a booking 14-day hiking trip through Visit Masoala, a local two-man operation, covering the island of Nosy Mangabe, Masoala, Marojejy, and Anjaharibe-Sud, with a few extra days to travel and explore Tana. It was ambitious, but not impossible.

Getting to Antananarivo from Geneva is relatively simple and inexpensive on Air France, who operate a nine-hour once daily flight from Paris to Antananarivo. We landed in Tana at 11pm and waited in a long line for our arrival visa. By the time we picked up our bags we only had a few short hours to get some rest before an early morning flight north. We had booked a room in the simple but clean Homelidays hotel, located just a 5 minute walk from the airport. Willy, the owner, welcomed us warmly and offered to escort us back to the airport at 4am. It felt like we had just fallen asleep when our alarm went off, but we trudged back to the airport for a 6am flight to Sambava, followed by a flight to Maroantsetra, where we would begin our adventure.

Air Madagascar has a reputation for significant delays and cancellations, many times without warning, so we prepared ourselves for the worst. But much to our surprise, we experienced almost no glitches with any of our flights. Our plane to Sambava was a 30 person propeller plane that put us slightly on edge, but it was a smooth and fascinating flight as the rising sun revealed a barren otherworldly landscape of red undulating hills. Madagascar’s laterite soil gives it this red color, which has been exposed now due to slash and burn agriculture, leading to its appropriate nickname as “the red island”. Our second flight made the first plane look like a brand-new jumbo jet. With trepidation, we boarded a 10-person plane that appeared to be a set of old school bus benches squeezed into the shell of a small, fragile propeller plane. Of the 12 passengers, seven of us had traveled from Switzerland – apparently the primary place where people are adventurous and fit enough to brave the jungles of Madagascar.

As the wheels touched down in Maroantsetra, everyone on the plane let out a collective sigh of relief. After two men wheeled in our bags on a cart, a taxi driver who had been waiting with our name written on a piece of paper led us to his ancient car. The partially paved bumpy road from the airport led straight into town and gave us a snapshot of the area as we drove along, passing rice fields, zebus (cows), clusters of palm thatched huts and a steady stream of people walking up and down the road – the women carrying baskets on their heads, the men carrying loads on their shoulders. We soon stepped out of the car at the Coco Beach Lodge, a traditional bungalow style hotel located on the river in the center of town, where Lauriot, our trip organizer who doubles as the head of tourism for Masoala National Park, was waiting. Already feeling the impact of the unpredictable wet weather, we found out that our overnight on Nosy Mangabe island was delayed by a day due to choppy seas, and we would instead spend the night in Maroantsetra. After lunch in the hotel restaurant, on a wooden pavilion overlooking the water, we met with Lauriot and Claudio, our guide for the rest of the trip, and reworked our schedule for the coming weeks. We would just have to hike faster.

In the afternoon Claudio took us on a tour of Maroantsetra. Knowing our interest in wildlife, he led us through a maze of produce, fish and meat at the sprawling village market to his friend’s backyard, where two tomato frogs had been spotted under his tree. Aptly named for their large size and bright red appearance, the frogs are endemic to the town and well worth seeking out. Just above them, Claudio peeled back a branch to reveal a completely camouflaged panther chameleon, its eyes pointing heavenwards, trying its best not to let us see it. Just then, the skies broke loose and we were quickly soaked, a feeling that would become all too familiar in the coming weeks, sending us hurrying back to the hotel.

Our boat picked us up from our hotel the next morning with a crew of 6 – two cooks, a guide, a captain, and two porters. Thirty minutes later, we pulled into shore on a sandy beach amidst the dense, misty jungles of Nosy Mangabe, where we would camp for the night. Nosy Mangabe is a small island, easily walkable from end to end in a few hours, that boasts an incredible array of wildlife, including the critically endangered black and white ruffed lemurs, aye-ayes, white-fronted brown lemurs, tiny brookesia chameleons, and the bizarre-looking giant leaf tailed gecko. For anyone who finds themselves in the area, it’s a must, and an overnight stay is recommended. While our porters set up our tent, Claudio wasted no time in leading us on a hike to the highest point on the island before lunch. Minutes later, we were on a scavenger hunt for brookesia, finding found four. Halfway up the trail, a telltale call allowed Claudio to spot a rare black and white ruffed lemur peering curiously at us through the leaves on a branch above us. We continued on, stopping occasionally when Claudio pointed out an interesting frog, plant, or bug. Reaching the bottom of the trail near our campsite, Claudio told us this was prime Uroplatus, or leaf-tailed gecko, territory based on the type of tree and its affinity for flat ground. We walked along slowly, keeping our eyes peeled, and it wasn’t long until Claudio pointed to a tree and asked “can you find it?” This time we succeeded and ran over to the giant leaf-tailed gecko sleeping upside down at eye level. It was the most bizarre looking creature I had ever seen – it had swirly eyes that made it appear hypnotized, and frills on its chin and abdomen that allowed it to press itself against the trunk as though it were made of plasticine and someone had pressed it around the edges with their thumb.

Our boat picked us up from our hotel the next morning with a crew of 6 – two cooks, a guide, a captain, and two porters. Thirty minutes later, we pulled into shore on a sandy beach amidst the dense, misty jungles of Nosy Mangabe, where we would camp for the night. Nosy Mangabe is a small island, easily walkable from end to end in a few hours, that boasts an incredible array of wildlife, including the critically endangered black and white ruffed lemurs, aye-ayes, white-fronted brown lemurs, tiny brookesia chameleons, and the bizarre-looking giant leaf tailed gecko. For anyone who finds themselves in the area, it’s a must, and an overnight stay is recommended. While our porters set up our tent, Claudio wasted no time in leading us on a hike to the highest point on the island before lunch. Minutes later, we were on a scavenger hunt for brookesia, finding found four. Halfway up the trail, a telltale call allowed Claudio to spot a rare black and white ruffed lemur peering curiously at us through the leaves on a branch above us. We continued on, stopping occasionally when Claudio pointed out an interesting frog, plant, or bug. Reaching the bottom of the trail near our campsite, Claudio told us this was prime Uroplatus, or leaf-tailed gecko, territory based on the type of tree and its affinity for flat ground. We walked along slowly, keeping our eyes peeled, and it wasn’t long until Claudio pointed to a tree and asked “can you find it?” This time we succeeded and ran over to the giant leaf-tailed gecko sleeping upside down at eye level. It was the most bizarre looking creature I had ever seen – it had swirly eyes that made it appear hypnotized, and frills on its chin and abdomen that allowed it to press itself against the trunk as though it were made of plasticine and someone had pressed it around the edges with their thumb.

There was one other family on the island touring with Masoala Forest Lodge, one of the upscale lodges in Masoala, and we all headed to the picnic area for lunch. The tables were laid side-by-side; Masoala Forest Lodge’s setup looked like a scene from a magazine, decorated beautifully with a checked tablecloth, napkins, and colored glassware, whereas ours, in stark comparison, was laid with a simple white cloth and paper napkins. We all sat down. Their guide opened a container lunch to reveal a simple rice salad – an easy and sufficient picnic lunch. We watched them enjoy their meal, and then watched the look change to envy as our chef brought out a first course of homemade beef and rice noodle spring roles with preserved lemon and chili sauce, followed by a second course of freshly caught fish steak and potatoes a gratin, and a third course of fresh local bananas. Bananas are popular with many inhabitants of the island, and as soon as we began to peel them, we were visited by a group of white-fronted brown lemurs who wanted us to share, and were not above dumpster diving to try to find the leftovers.

After lunch we set out on another trail, veering off into the jungle for another black and white ruffed lemur sighting, and eventually turning back when it started to rain. We took shelter under a palm thatched bungalow just feet from the ocean, where our tent had been set up for the night. We were the only ones staying on the island and had the entire campsite to ourselves. Our cook brought over a cold Three Horses beer and fresh roasted local peanuts as a prelude to dinner, which turned out to be another gourmet meal eaten by candlelight, since dark sets in by 6pm. While we ate, we were entertained by clapping and singing drifting from the kitchen – our crew and the park ranger stationed on the island were singing a special song to protect the lemur.

It was a restless night thanks to the incredibly loud collection of sounds coming from a host of lemurs, frogs, rodents and insects, and large waves crashing on the shore. At first light we dragged ourselves out of bed for a quick breakfast of toast and jam, then jumped back on the boat before the seas got any rougher for a two-hour, bumpy ride to Masoala National Park. Crashing over waves, the plastic boat sounded like it might crack in two at any minute. We lost sight of land as a huge storm poured down on the park, but we were soon distracted by a pod of humpback whales that took turns rising up beside us, slapping their tales and spouting huge streams of water. It was a huge relief when we docked at the Hippocampe Lodge, one of the four (soon to be five) lodges built on the coast in Tampolo, in the middle of the park.

The lodge consisted of a set of new, simple palm thatched bungalows with beds and private bathrooms, and a small common lounge bungalow with a kitchen. We were the only guests there – our plan was to spend two nights in the lodge in order to do some day hikes around the trails where red ruffed lemurs are commonly spotted, before embarking on a three-four day hike through the jungle and along the coast, around the tip of the Peninsula to Cap Masoala, where we would catch a motorbike ride up to Sambava. Hippocampe is currently the closest lodge to the quaint village (about 10 minutes walk) and main marked trails of the park (about 30 minutes walk), where red ruffed lemurs, the park’s signature lemur species, are known to hang out. We went for a total of three hikes through this part of the park, mostly in the pouring rain, and managed to catch a wet glimpse of the red ruffed lemurs sitting high up in the trees, along with some kingfishers and flycatchers. In the evenings we would dine on incredible dinners of local shrimp and fish prepared by our very talented chef, then sit in the common area and read to the sound of crashing waves. One night as we were reading in the dark, Claudio ran in shouting “tenrec!!” and plopped a silver mixing bowl down in front of us containing another one of the strangest creatures I have ever seen – a streaked tenrec. Claudio had caught it with his bare hand, which now looked like an odd sort of cactus covered in yellow spikes. The poor tenrec was terrified, but we couldn’t stop looking at it. With its spiky black and yellow striped pear-shaped body and crown of yellow spikes, it looked like the lovechild of a hedgehog, mole and bumblebee.

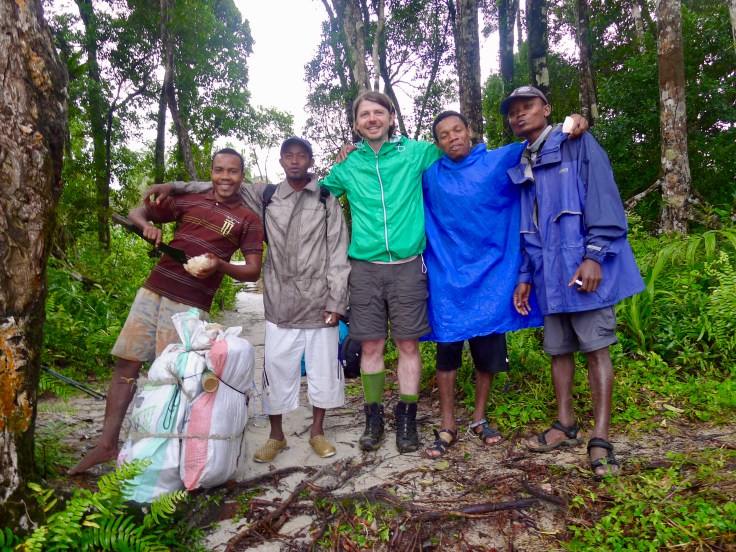

On day three, we set out for our multi-day hike around the peninsula with a guide, cook, and two porters by our side. The hike began in a torrential downpour but the sky soon cleared and lit up a coastline of sandy shores and blue water studded with huge black stone formations, the jungle coming right up to the sea. There were formal trails during some legs of the journey, though many segments involved expert navigation by our guide and porters through rivers, ocean crossings, and mangrove marshes. We must have forged over 10 rivers, ranging from thigh to chest deep, thanks to the unprecedented rains of the past few days.

Lunch was served in a communal kitchen, pots burning on a fire behind us, in an idyllic tropical village surrounded by palms, vanilla plantations, and cow pastures in the middle of Masoala. Not long after departing the village to complete the rest of our hike, we reached an impassable river. We watched a woman remove her basket from her head and float it next to her while she swam across, but this strategy was out of the question for us thanks to our backpacks and food. Instead, we hiked farther up the banks along a thick mud trail to a “ferry” crossing – a bamboo raft attached to a rope would shuttle us across. We took turns being pulled across the water, barely staying afloat under all the weight, and continued on the other side.

At dusk we arrived at our campsite, a small clearing on the coast next to an isolated home. The porters set up our tent under a tarp, in case of rain during the night (which was a guarantee) and then set up a makeshift table and chairs on the beach so we could relax with cold drinks and watch the sun set over the water while dinner was prepared.

For dinner, we were invited into the small home on the property, the length and width of a single bed, but containing the bedroom, living room and kitchen of the owner. We sat on the bed and were served another three-course meal of potato salad, zebu kebabs with roasted potatoes, and coco bonbons (an incredible concoction of freshly grated coconut cooked with vanilla beans and sugar until it caramelizes into a hard ball) for dessert, all cooked over a fire in an adjacent shelter. After a brief, uneventful night walk we settled into our tent for the night, only to be awoken in the middle of the night by rain coming through the wall – our tarp had some loose in a torrential windy downpour. The only solution was to brave the rain and fix it. It was a wet, cold rest of the night.

The second day of the hike would be our longest. Nine hours through thick, rarely maintained jungle trails with many rivers to cross. Though the clouds had parted for breakfast, our hike quickly turned into a slog through trails of ankle-deep mud rivers and waterfalls and waist-high water crossings, as what felt like a monsoon poured down on us. We struggled to keep going, trying not to think about nine more hours of these conditions. After pushing our way through a long stretch of thick jungle brush, we reached a raging stream about eight feet wide and at least waist deep that would require us to make a human chain if we wanted to cross, and even then it would be dicey. Claudio had never seen the water this high at this time of the year, and this first stream was smaller than many of the subsequent crossings. He and our porter made a judgement call that it was too dangerous to continue the hike today. At that point we were already soaked, muddy, scared, and exhausted, and were more than happy to retreat.

The second day of the hike would be our longest. Nine hours through thick, rarely maintained jungle trails with many rivers to cross. Though the clouds had parted for breakfast, our hike quickly turned into a slog through trails of ankle-deep mud rivers and waterfalls and waist-high water crossings, as what felt like a monsoon poured down on us. We struggled to keep going, trying not to think about nine more hours of these conditions. After pushing our way through a long stretch of thick jungle brush, we reached a raging stream about eight feet wide and at least waist deep that would require us to make a human chain if we wanted to cross, and even then it would be dicey. Claudio had never seen the water this high at this time of the year, and this first stream was smaller than many of the subsequent crossings. He and our porter made a judgement call that it was too dangerous to continue the hike today. At that point we were already soaked, muddy, scared, and exhausted, and were more than happy to retreat.

However, this meant some serious rearranging of plans. In order to make it to all of the parks on our trip, we would not have time to wait for the weather to clear and hike the next day. Instead, our best chance was to go back the way we came, by boat to Maroantsetra and flight to Sambava, both of which we had sworn never to do again. It was Monday, and flights to Sambava only left on Wednesdays and Sundays. Lauriot, our tour organizer quickly booked us tickets on the Wednesday flight, and Claudio set a quick pace to get us back to the nearest lodge before dark, where we would take a boat to Maroantsetra the next morning.

As luck would have it, the rest of the day was beautiful, the sun making periodic appearances through fluffy white clouds. Near the end of our hike we were running low on water, so our porters stopped in a village, climbed a palm tree, and picked us two coconuts that they quickly turned into beverages with their machetes. Even more miraculously, while we waited on the beach for them to return, a giant sea turtle stuck its head out of the water right in front of us. We watched it do laps as we sipped our coconut water, then hurried to finish our hike before dark. As dusk settled in, we arrived at Tampolodge, a beautiful property owned and run by an Italian man and his brother, who had married a local woman. The lodge was everything we’d ever wanted – it was exquisitely constructed of dark red wood and palm, with spacious well-appointed private bungalows nestled among vanilla vines, cloves, and palm trees. After a glorious hot shower, we sat down in the cozy loft area of the dining room with Claudio and asked him all our questions about local life in this part of Madagascar.

Our chef, Julienne, eventually called us down to a formally set table and proceeded to serve us a mind-blowing meal. The first course was a hot soup of roasted root vegetables with fresh homemade buttered croutons. It is a mystery as to how he blended a totally smooth soup in such a rudimentary kitchen, but it was excellent by any standard. Next came perfectly grilled chicken legs in a soy barbecue sauce accompanied by roasted vegetables. This was followed by freshly grated coco bonbons, which he knew were our favorite, and tea.

In the morning, Julienne served us breakfast on a private platform with just one table located directly on the water. He had gotten up at 5am to walk 30 minutes to the nearest village, which included forging a river twice, just to get us fresh bread that he then served with fried eggs and perfectly presented delicate crepes that looked as though they came from a fancy brunch restaurant in the city.

The owner of the lodge came by and introduced himself after breakfast, warning us that taking a boat back to Maroantsetra right now would be very dangerous and we would face a good chance of capsizing in the ocean. He suggested we stay one more night and take a boat at 5am the next morning when the sea would be calmer. This meant risking our 10am flight, and there wasn’t another flight for 4 more days. Our guides told us “from their hearts” that the ocean was fine, and both parties insisted that the other was just out to make money. Eventually, we decided to trust our guide and got on the boat. Although the ride was probably smoother than on the way there, we had the terrifying seed planted in our minds that we might not make it across, and each wave brought fresh fear that we might soon be swimming. A series of breaching humpback whales helped take our minds off of the sea, and a hole in the sky had opened like an eyelid, keeping us in direct sunlight the entire way though storms surrounded us on all sides. After two anxious hours we arrived back on land. This time we stayed in Manga Beach hotel, a new building with big beds and showers, though lacking the charm of Coco Beach.

The owner of the lodge came by and introduced himself after breakfast, warning us that taking a boat back to Maroantsetra right now would be very dangerous and we would face a good chance of capsizing in the ocean. He suggested we stay one more night and take a boat at 5am the next morning when the sea would be calmer. This meant risking our 10am flight, and there wasn’t another flight for 4 more days. Our guides told us “from their hearts” that the ocean was fine, and both parties insisted that the other was just out to make money. Eventually, we decided to trust our guide and got on the boat. Although the ride was probably smoother than on the way there, we had the terrifying seed planted in our minds that we might not make it across, and each wave brought fresh fear that we might soon be swimming. A series of breaching humpback whales helped take our minds off of the sea, and a hole in the sky had opened like an eyelid, keeping us in direct sunlight the entire way though storms surrounded us on all sides. After two anxious hours we arrived back on land. This time we stayed in Manga Beach hotel, a new building with big beds and showers, though lacking the charm of Coco Beach.

In the morning we held our breath got on the same sketchy plane to Sambava, this time with Claudio, who would act as the “supervisor” for the rest of the trip. A rickety taxi transferred us the short distance from the airport into downtown Sambava, where we were dropped off at Hotel Mimi. The torn up appearance of the entrance in a busy part of town was off-putting, but the rooms were clean and there was a mediocre restaurant attached where we could have lunch and dinner. Our main priority for the day was to dry our clothing, most of which was once again soaked. Our taxi driver lent us some rope which we used to hang out clothes on the porch while pointing our room fan on them to stir up a breeze. Then we went off to explore the city.

Sambava is a relatively spread out town that feels chaotic, but is easy to explore by foot. It is one Madagascar’s main vanilla exporting towns and also home to the Duke Lemur Center Madagascar Office. It was raining with no sign of letting up, and our taxi driver offered to chauffeur us around for the afternoon. Our first stop was the little boutique Maison de la Vanille to buy some high quality vanilla, while also seeing the process of preparing and distributing the beans. Madagascar supplies 80 per cent of the world’s vanilla, due to the absurdly cheap cost of labor needed to facilitate the intensive process required to hand pollinate each flower, and is currently in the grip of a vanilla boom due to strong demand, a cyclone that destroyed many crops in 2017, and money laundering. Only five years ago, vanilla was trading at $20 a kilogramme, whereas now it goes for $515. People are trading crops that could feed their families, like rice and manioc, for vanilla, and those that have already cashed in on their vanilla crops are buying cars and motorbikes that they won’t even be able to fill with gas when the price of vanilla inevitably crashes.

The owner of Maison de la Vanilla seemed surprised by the request to tour the vanilla process, but kindly allowed us into the back warehouse to examine the vanilla drying at various stages, before being packed into boxes and shipped to Tana for export across the globe. Then it was on to the Duke Lemur Center, where we were able to speak with the project manager about their research in Marojejy national park before a quick dinner and early bedtime.

After some thick but tasty chocolate croissants the next morning, the same taxi that had taken us from the airport picked us up for the drive to the Marojejy and Anjaharibe Sud park office, where we would begin our next hike. Luckily this was a vanilla road, which meant it was paved and well maintained, and the car didn’t have any issues, though our backpacks and supplies for the hike barely fit inside. Just before the park office, we picked up a pineapple from two young boys selling them at a roadside stand to have with dinner that night. We soon pulled into the office and were greeted by our new local guide Reese, a cook, and two porters. While the porters sorted the food and bags, we set off with Reese for the park. One path leads from the entrance of Marojejy to the summit of Mount Marojejy, the highest peak in the park and many people’s final destination, though not ours. There are three camps along the route: Camp Mantella at 450m elevation in lowland rainforest, Camp Marojejia at 775m at the transition between lowland and montane rain forest, and Camp Simpona at 1,250m in the middle of the montane rainforest. Camp Simpona serves as a base camp for the trek to the summit, which can take four or five hours. Our destination for the night was Camp Mantella, a five-hour hike from the park office.

The first two hours of the hike, from the park office to the park entrance, traversed many local villages, rice paddies, and treeless hills on a muddy red dirt road. The park entrance is quite obvious because all of a sudden, we were in the jungle. From the park entrance it was another two-three hour hike through the jungle to our campsite. The Duke Lemur Center recently built facilities in all three campsites in hopes that it would draw tourists and boost the local economy, so each one is now equipped with a toilet, set of green tarp bungalows and bunk beds, and a covered platform with kitchen equipment and picnic tables.

At some point during our hike, we realized that we had entered the leech zone of the park. We had been warned about leeches, but Malagasy land-dwelling leeches are very different from what I had previously understood leeches to be – fat ugly creatures that look like slugs and live in the water. I mistook the first Malagasy leech I found crawling up my pant leg for an inchworm. Both are about the same shape and size, and inch along in the same way, only the leeches are brown and slimy and have 300 tiny razor sharp teeth that they use to latch on to the first patch of soft skin they find, making tiny cuts and injecting an anticoagulant and anesthetic to keep their victims bleeding freely and pain-free. However, there was no mistaking the vast amounts of blood pouring out of my shoes as we neared the campsite – it was definitely a mistake to wear water shoes with holes and no socks. I almost couldn’t bear to take my shoe off, but the feel of leeches squishing under my toes, and the copious blood covering my shoe was making me queasy, so just before the campsite I pulled of my sandal. There was blood everywhere, but Reese was a hero and immediately rushed over and pulled off all eight leeches attached to my foot, which had started to resemble a sieve. We hurried to the campsite, where I was able to wash my legs and put on two layers of insect repellent socks under my shoes, in hopes they would also ward off leeches.

It had been raining for three days straight with no sign of sun, and no sign of letting up, and almost everything we owned was still wet. A fire seemed the obvious solution, but the campsite only supplied gas for cooking. We asked our guide how much it would cost to commission a bag of charcoal to be brought up the mountain by a porter in town – he made a phone call and visibly cringed as he relayed the price: 30,000 ariary, or about 7 dollars. We didn’t have to think twice – there would be a fire burning by the time we were back from our hike the next morning.

It was already late afternoon by the time we recovered from the first portion of the hike, but it was still light enough for a short jaunt further up the mountain. Just up the trail, I glanced towards the canopy and noticed a tail hanging from a stalk of bamboo. Upon further investigation, we discovered a group of four fuzzy Northern Bamboo Lemurs happily munching on leaves not far above our heads. Bamboo lemurs have round faces with huge black eyes and tiny ears that make them particularly adorable. They let us observe them until we decided it was time to head back for dinner; when we returned, another group of bamboo lemurs was playing in the bamboo branches by the kitchen. A bright red ring-tailed mongoose was also lurking nearby, repeatedly making a dash for the picnic table to steal a few scraps of food when he thought we weren’t looking, before running back into the bushes.

After a heavy platter of fried zebu and grilled vegetables and potatoes by candlelight, I turned on my headlamp and followed Reese down the now pitch-black trails in search of nocturnal life. Nightwalks are technically illegal in the national parks, due to a high amount of stolen animals, and our guides strictly adhered to this policy; however, a perk of staying inside the national parks is that we were allowed short excursions around the campsites. So we scanned every tree, branch, and bush in the vicinity with our headlamps, looking for the telltale glowing eyes. Three large pink and green frogs blinked back at us as they clung sideways to a series of bamboo stalks, but we were out of luck for any mammals or leaf-tailed geckos.

The rural Malagasy rise and sleep with the sun, so by 7pm it was past bedtime – we read by headlamp for a few minutes, then crawled into our sleeping bag liner and let the sounds of a million frogs lull us to sleep. In the morning we set out for camp Marojejia, about two hours further up the mountain in an area of the park that the park’s flagship species, the silky sifaka, is particularly fond of. Our mission for the day was to find them. It was pouring out, and we took a brief reprieve when we made it to camp while Reese went in search of the local “tracker” we had hired – his job was specifically to wake up and search for silky sifakas, and then lead us to them. It wasn’t long before Reese returned. “They’re 700 meters above us” he said, “let’s go”. Seven hundred meters above us meant literally straight up through a thick patch of jungle with no trail. But it was worth it. When we reached our tracker, a short, jovial man whose name translated to January, he was grinning at us and pointing to the tree above – there sat three beautiful silky sifakas. Two more soon swung over and joined them, and the five of them sat in front of us, casually picking leaves and grooming themselves, while we watched in rapt attention. The silky sifaka is one of the five most critically endangered primates in the world, with under 1000, and likely closer to 200 animals remaining. They have gorgeous silky white fur, and funny but remarkably human looking pink faces with big black eyes. They are known for being able to leap up to 30 meters between trees, but when they come down to the ground they hop across it on two legs, giving them the nickname “dancing sifakas“. After a while, we saw their skills in action as they soared to a set of trees even closer to our observation spot. Two hours later, in the pouring cold rain, they finally flung themselves out of sight, and we decided to head back to the campsite for lunch. Just before we arrived, our luck continued and Reese excitedly turned us to face an elusive helmet vanga, resembling a toucan with a brilliant blue beak, that had landed on a nearby branch at eye level. It posed for a few minutes before flying off into the mist.

A huge bag of charcoal was waiting for us by the time we arrived, and within minutes our cook had two ceramic pots blazing, plopping one in front of each of us on the covered platform. Chris hung our wet clothes on benches around the fire and propped his boots up next to the hot coals to dry. The rain still hadn’t let up, and we were fully satisfied with our sifaka sighting, so we let the fire burn on for the next seven hours while various members of our crew took turns coming to sit with us and keep warm.

We awoke to a foreign sight – bright sunlight was illuminating all of the surrounding mountains, exposing huge granite cliffs that soared up above the canopy. Rejuvenated by the clear sky, we hit the trail back to town early, taking a minute to swap stories with a couple Americans from New York City whom we passed towards the end of the trail. They were traumatized – they had come unprepared for such difficult hiking conditions, without socks or long pants, and spent four days wet, cold, and covered in leeches, and didn’t even see the silky sifakas. At the edge of the park we walked into what appeared to be a totally different town than the one we had passed just days earlier. There was now a festive atmosphere thanks to the reappearance of the sun, and brilliantly colored clothing covered every available surface, turning the village into a beautiful patchwork quilt set against the mountains. The air smelled of vanilla, as villagers’ crops of rice, vanilla, coffee, and peanuts were laid out to dry in front of their houses.

From the edge of town we had a beautiful view of Mount Marojejy rising up from the middle of the park with green rolling mountains spreading out around it. A 4×4 vehicle, no doubt purchased with vanilla money, picked us up partway through our walk, stopping briefly at the park office to pick up the rest of our crew, before heading towards Andapa, a small friendly town where we would spend the night before our last hike of the trip in Anjaharibe Sud. We pulled over for lunch at a local restaurant, filling up on rice and beans washed down with a cold coco cola. The drive from Marojejy to Andapa was stunning, winding through a green mountainous landscape dotted with neon rice fields and small villages where families were in the rivers bathing and doing their laundry in the blessed sun.

In late afternoon we reached Andapa, a bustling compact town set in a beautiful location reminiscent of Geneva, with mountains rising up on all sides. Our introduction to Andapa began as a fiasco, when we learned that our tour company had failed to book us a hotel room, and every single room was full thanks to a Daddi Love concert that night. The initial, and at that point only, solution was a dirty room across from a wall of drying meat that shared a somewhat open wall with a pigpen – we could actually see the pigs. After many phone calls, our guides were able to resolve the problem and as dusk fell, we stuffed ourselves and our packs into a tuk tuk and rambled down a long dirt road to the other side of town, where we were dropped off at a remote hotel with a clean room that seemed to have had few, if any, tourists ever stay there before.

Putting the experience behind us, we woke up grateful for another sunny morning and joined our crew in the 4×4 headed to Anjaharibe Sud to begin a long hike in the hot sun. We parked in a small village; though the road continued, it had turned into a huge red trough of mud that was inaccessible by most vehicles. This red mud trough was our path for the entire six-hour hike up to our campsite, which lay just 200 meters off the road inside the park. Despite the arduous hike, the day turned out to be one of our favorite experiences of the trip. We passed men, women, and children carrying a fascinating variety of items in incredible ways: women with baskets of live ducks on their heads; men pushing bicycles loaded with grains, vanilla, or furniture; children with machetes, zebu, and bananas.

We hiked through numerous villages that had rarely, if ever, seen “vazaha”, or foreigners, before, practicing our “salama zazekily” (hello kids) and “envovo” (what’s up) as we went, much to some of the villagers’ delight. The children, on the other hand, usually ran away crying in fear as soon as they saw us. Our guide translated one woman’s comment to her child before he broke down: “that’s a white person. They’ll eat you”, which she thought was hilarious, but her child did not. We stopped to sip coffee from a woman brewing local beans in a small thatched shelter, then carried on until lunch, where we ducked into a tiny restaurant for rice and beans. Dessert was a piece of jackfruit from the tree across the street. We handed our hiking poles and camera to a group of kids who had been watching us through the window, which entertained them greatly while we ate. Their toys were even cooler we soon realized, as we watched a group of boys zip by us down the mountain on a homemade wooden boxcar-tricycle hybrid.

Nearing our campsite, we passed a large group of men and women carrying various items on their shoulders and heads coming the opposite direction, and were able to speak with them thanks to our guide. We learned that what seemed like a long day for us was nothing compared to what they were enduring – they were on a five-day hike from their small villages to Andapa to sell their products at the market and work in the rice fields to feed their families. After a couple months they would go back, and then repeat the journey four more times that year.

Exhausted, we entered our campsite and were immediately impressed. Four sturdy new tent shelters, a picnic area with cooking facilities, and a pit toilet had been built in recent years by the Duke Lemur center, and along with them they had left camping supplies in a locked shed. Our crew picked out a huge REI tent and some sleeping mats for themselves, and we eagerly jumped on two thin sleeping pads to replace the rubber raft-looking “mattresses” we had attempted but failed to sleep on during our previous nights in a tent. Much to our dismay, it didn’t take long to realize that this park also had leeches, as we discovered them crawling up our pants. It was already late, so we read at the picnic tables until dinner, and then crawled into bed. No sooner had I laid down, than I was startled by a leech that had gotten under my shirt and was biting my back. Traumatized, we stayed awake the rest of the night thanks in part to the leeches, but mostly because of the loud crashes coming from the brown fronted lemurs jumping through the trees around our tents and a chorus of other howling, hooting, scratching and chirping creatures.

The next morning we awoke with one goal: to see the mythical indri, the largest currently living lemur. The plan was to have breakfast while our tracker, a local expert in spotting the indri, went out in search of a group. When he found them, he would call to us or come get us and bring us to them. But we were antsy with anticipation, so immediately after breakfast we started down a trail to kill time until we were summoned. Reese stopped suddenly and we grew quiet – from out of nowhere, an eerie song floated over our heads – the surreal call of the indri. We were lucky, and there were multiple groups in the park who began calling back and forth across the park to each other, letting us bask in the other worldly sounds. It also let our tracker identify their location, which happened to be very close to where we were standing. He called out for us and we ran up a hill to find him. At the top we found ourselves on the edge of a steep slope at the top of the canopy, standing almost eye to eye with a group of indris lounging in the tops of their favorite trees. It was magical to see this marvelous animal up close. They were so large, with such human postures, and staring back at us with soul-piercing light eyes, that it was impossible not to feel like they were just human beings dressed in costume. Neither we nor the indris could stop watching the other, so we stared at each other for nearly an hour, the indris taking breaks to snack, until finally they made their way down the slope and out of sight.

As a last hurrah we went for one final hike in the afternoon, randomly choosing a trail with no expectations of seeing anything in particular. But soon Reese whispered sharply, “indri! look up!” and there, sitting just above us in a treetop, watching us carefully the whole time, was an indri. He was high above us, but through our binoculars we could see him struggling to stay awake, his eyelids drooping and eyes periodically closing like a tired kid in a classroom. We eventually left him alone to rest and turned around. On our way back, Reese again pointed up whispering “silky sifaka!”, and sure enough, a group of silky sifakas was nestled in the branches of a nearby tree, close enough to see clearly.

We got an early 6am start the next morning to make it all the way back to Sambava for the evening before our flight to Tana the following day. It was much easier going down than up and we made good time. Partway down we stopped for a snack. Two young women had set up a small wooden stand and were busy frying various types of dough – we ordered six banana beignets and sat down on a bench behind them to wait. We watched the dough sizzle in a wok of hot oil set on a burner in front of us, and were soon handed a plate of steaming fried balls. A wave of deliciousness washed over my tongue as I bit into the first ball – slightly crunchy on the outside, chewy and moist on the inside, and tasting exactly like fried banana bread. We were hooked. After devouring two full plates in front of a crowd of onlookers, we heaved ourselves up and continued down the mountain. An hour from our destination the road shifted steeply uphill for a short section. By this time the sun was blazing, and it was hot. As we huffed and puffed, carrying nothing but binoculars, we passed two teenagers struggling to push a bike loaded with large wooden beams up the hill. Our guide immediately jumped in, pushing the beams from behind. Eventually he, too, was exhausted and had to stop, so Chris took over. After getting them close to the top, he also had to stop, panting, on the side of the road to catch his breath.

We got an early 6am start the next morning to make it all the way back to Sambava for the evening before our flight to Tana the following day. It was much easier going down than up and we made good time. Partway down we stopped for a snack. Two young women had set up a small wooden stand and were busy frying various types of dough – we ordered six banana beignets and sat down on a bench behind them to wait. We watched the dough sizzle in a wok of hot oil set on a burner in front of us, and were soon handed a plate of steaming fried balls. A wave of deliciousness washed over my tongue as I bit into the first ball – slightly crunchy on the outside, chewy and moist on the inside, and tasting exactly like fried banana bread. We were hooked. After devouring two full plates in front of a crowd of onlookers, we heaved ourselves up and continued down the mountain. An hour from our destination the road shifted steeply uphill for a short section. By this time the sun was blazing, and it was hot. As we huffed and puffed, carrying nothing but binoculars, we passed two teenagers struggling to push a bike loaded with large wooden beams up the hill. Our guide immediately jumped in, pushing the beams from behind. Eventually he, too, was exhausted and had to stop, so Chris took over. After getting them close to the top, he also had to stop, panting, on the side of the road to catch his breath.

With fifteen minutes left in our hike, we gave Reese the challenge of finding three chameleons. Within five minutes, he had spotted three and Chris had spotted one. Finally, we reached the village and bought some freshly cut bananas and homemade peanut brittle to snack on while we waited for our ride. A different 4×4 soon came and scooped us up, and we began the three-hour drive back to Sambava. We stopped in Andapa for a lunch of rice and fried fish at a small wooden restaurant before finishing the drive. The weather was still beautiful and the sinking sun was casting a golden hue over the mountains and rice fields.

In Sambava we had chosen to stay at Orchidea Beach II Hotel. We were hoping it would be nicer than our last hotel – at the very least, a place where we could shower, wash off the leeches, and relax a bit now that the hiking portion of our trip was over. We drove through town and eventually turned left down a small alley with a huge unfinished concrete building with rebar sticking out of the top looming on one side. Preparing for the worst, it was a wonderful surprise when we turned again and parked in front of a lovely lush courtyard sitting right on a beautiful stretch of sandy beach, the sun just beginning to set over the water. Our amazement continued as we were shown to our room, decorated in a stunning combination of blue tile and dark wooden beams, with a huge modern bathroom and a terrace looking out over the garden and ocean beyond. It was everything we could have ever dreamed of upon returning from the jungle, and it was only $20 a night.

We bought our guides a beer and took a walk down the beach before saying goodbye and heading inside for a hot shower. The relief of knowing that we would stay clean for the rest of our trip and no longer had to check ourselves for leeches every five minutes made us giddy. We celebrated with dinner at the hotel restaurant – coconut rice and fresh shrimp and zebu kebabs, followed by caramelized fresh bananas in a burnt sugar sauce. At 10pm it was way past our bedtime and we were soon fast asleep.

After two rounds of crepes at the hotel for breakfast, we headed to the airport and caught our flight to Tana. A driver from our hotel picked us up in a fancy new SUV for the hour long drive into town. We passed through rice fields and towns lit up by the setting sun, before winding up up up through the streets of downtown Tana until we reached our hotel, La Varangue hotel and restaurant, in upper Tana. La Varangue is known as one of the best restaurants in town, serving a gourmet blend of French and Malagasy fare at extremely affordable prices, so we had made a reservation for both nights we were in town. Set in a beautiful colonial French mansion, La Varangue feels more like a museum than a hotel, with antiques and old photos covering the walls. We were handed a glass of freshly squeezed passion fruit juice at the bar when we arrived and then shown to an immaculate, airy room with a balcony overlooking the courtyard in front of the hotel. We freshened up and made our way downstairs to the restaurant, prepared to spend the rest of the evening lingering over our meal.

French culture has persisted at La Varangue, and dinner lasted three hours, spread out over three courses. The elegant dining room was full and the atmosphere cozy and casual, despite the high quality of the food and service. Most diners were dressed in hiking attire, with a couple tables of locals in suit and tie. The food was beautifully presented and delicious, a unique combination of flavors made with seasonal ingredients, but we experienced some culture shock going from jungle to refined dinner in just a day, and we ate with mixed emotions, knowing that the price of our meal would cover a week’s salary for our guides.

The last day of our trip was open. Our flight wasn’t until 1am the next morning, but, still recovering from the previous two weeks, we decided to indulge and spend a lazy day napping and relaxing in our beautiful room, which we were allowed to keep until 10pm for half price, with some small excursions into the city. We started with a leisurely breakfast on the balcony – fresh juices, coffee, eggs, fruit, and chocolate croissants. Then we read and napped until lunchtime, walking to a nearby cafe recommended by our guidebook. From there we walked down a busy set of stairs lined with vendors selling handicrafts of all varieties, a line of children begging for coins and haggling vendors closely following us. We landed in a crowded marketplace of white cloth stalls selling food and clothing, but soon decided to head back to the hotel. The amount of desperation was overwhelming and heartbreaking, and for lack of being able to help everyone we needed a break. We bought a beautiful carved wooden baobab from an old woman on our way, and after much persistence, refused a wooden instrument from a man who followed us for an hour, slowly lowering and lowering his price.

The last day of our trip was open. Our flight wasn’t until 1am the next morning, but, still recovering from the previous two weeks, we decided to indulge and spend a lazy day napping and relaxing in our beautiful room, which we were allowed to keep until 10pm for half price, with some small excursions into the city. We started with a leisurely breakfast on the balcony – fresh juices, coffee, eggs, fruit, and chocolate croissants. Then we read and napped until lunchtime, walking to a nearby cafe recommended by our guidebook. From there we walked down a busy set of stairs lined with vendors selling handicrafts of all varieties, a line of children begging for coins and haggling vendors closely following us. We landed in a crowded marketplace of white cloth stalls selling food and clothing, but soon decided to head back to the hotel. The amount of desperation was overwhelming and heartbreaking, and for lack of being able to help everyone we needed a break. We bought a beautiful carved wooden baobab from an old woman on our way, and after much persistence, refused a wooden instrument from a man who followed us for an hour, slowly lowering and lowering his price.

At the hotel we called a taxi to take us across the city to Lisy Art Gallery, a large collection of arts and crafts stores selling reasonable quality souvenirs of all varieties from around Madagascar. We stocked up on gifts to take home, and then caught a taxi back to the hotel before it got dark, as Tana is notoriously dangerous for tourists after sunset. Back at the hotel, the same man who had tried to sell us the wooden instrument earlier was waiting for us – he must have followed us home – and the pleading look in his eyes was so desperate that we gave in and bought one for 40,000 ariary, which was all we had left, a quarter of his original price. Struggling to stay awake, we sat down for one more meal at La Varangue – our last in Madagascar – and then it was time to go to the airport.

It was with serious effort that we got on the plane home. Both of us had contemplated changing our tickets to stay at least another week. There is so much more of the country to see, and who knows what land and animals will remain by the time we return? Madagascar currently sits at a tipping point, ready to either go tumbling down the path of no return, or make a decision to prioritize its natural resources and build up its economy through ecotourism. In 25 years it will be obvious which choice the government makes. We plan to return before then, and anybody who wants to see the incredible array of natural phenomena the country has to offer should too.

Madagascar is very interesting country. We just come back from there last month:) But we have different route with you.

Which route did you take? We really want to go back and go north to Ankarana, and south to the tsingy and all the parks!

We did a loop around the south going along the RN 7 down to Tulear and then making it up along some tracks (4w4 essential) to Morondawa from where you can hit the tsingy. and then back to tana before driving up to Nose Be – didn’t make it to Ankarana though.